Prostate Cancer Screening Part 1 - 015

It's complicated.

This newsletter is about all things prostate-specific antigen (PSA), including the controversy surrounding this blood test and the anxiety this test provokes in men, especially in men already diagnosed with prostate cancer. If there ever was a topic that matches the phrase, “it’s complicated,” this is it.

PSA is an enzyme made by cells of the prostate gland that helps sperm swim better. The level of this enzyme is measured with a blood draw because it leaks into the bloodstream. Even though the PSA test is used to screen for prostate cancer, other conditions besides prostate cancer can elevate PSA levels such as an enlarged prostate, inflammation, and infection.

This is partly why this test is controversial - even though an elevated PSA level can suggest prostate cancer, an elevated PSA level does not mean there is prostate cancer.

Once you find an elevated PSA blood level, the only way to know for sure if the cause is prostate cancer is to perform a prostate biopsy, which is an extremely invasive procedure and not without risk for serious complications such as urinary tract and bloodstream infections.

Doctors perform prostate biopsies in two ways. One is by sticking a needle through the perineum, the part of the body between a man’s anus and his scrotum. The other is by placing an ultrasound probe into a man’s rectum and sticking a needle through the rectum into the prostate gland. Both ways require the doctor to stick an ultrasound probe into the rectum to help visualize the prostate.

Prostate biopsies can be done under local anesthesia, spinal anesthesia, or general anesthesia. Most are done using a local anesthetic to numb the area. The downside is that if the doctor takes a long time to do the biopsies, the anesthesia can wear off, as in my case. So, what was an uncomfortable procedure turned into a painful procedure.

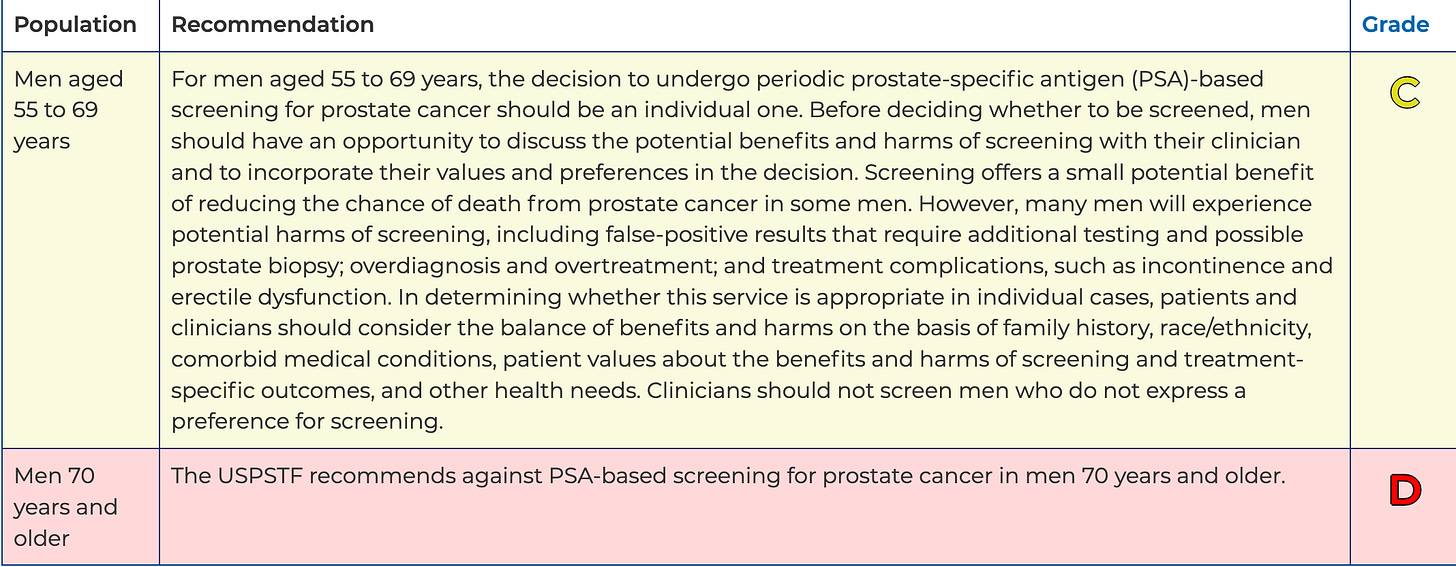

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an independent, volunteer panel of national experts in disease prevention and evidence-based medicine that makes evidence-based recommendations about clinical preventive services, including PSA screening.

In 2018, the USPSTF task force published their evidence report Prostate-Specific Antigen–Based Screening for Prostate Cancer, and concluded:

PSA screening may reduce prostate cancer mortality risk but is associated with false-positive results, biopsy complications, and overdiagnosis. Compared with conservative approaches, active treatments for screen-detected prostate cancer have unclear effects on long-term survival but are associated with sexual and urinary difficulties.

In other words, there is some evidence that using the PSA blood test in men to screen for prostate cancer may reduce the risk of death caused by prostate cancer, but PSA screening is associated with:

False-positive results - high PSA levels but no evidence of prostate cancer

Overdiagnosis - finds too many slow-growing prostate cancers that would not result in complications or death

Biopsy complications such as pain, bleeding, urinary tract infections, and serious bloodstream infections

Once prostate cancer is detected, active treatment is used appropriately in some men and inappropriately in others, which can result in impotence and urinary incontinence.

Because of these findings, the USPSTF made the following recommendation:

Their recommendations:

Consider PSA blood testing to screen for prostate cancer in men aged 55 to 69 only after discussing the potential benefits and harms of testing

Don’t perform PSA screening in men 70 years and older

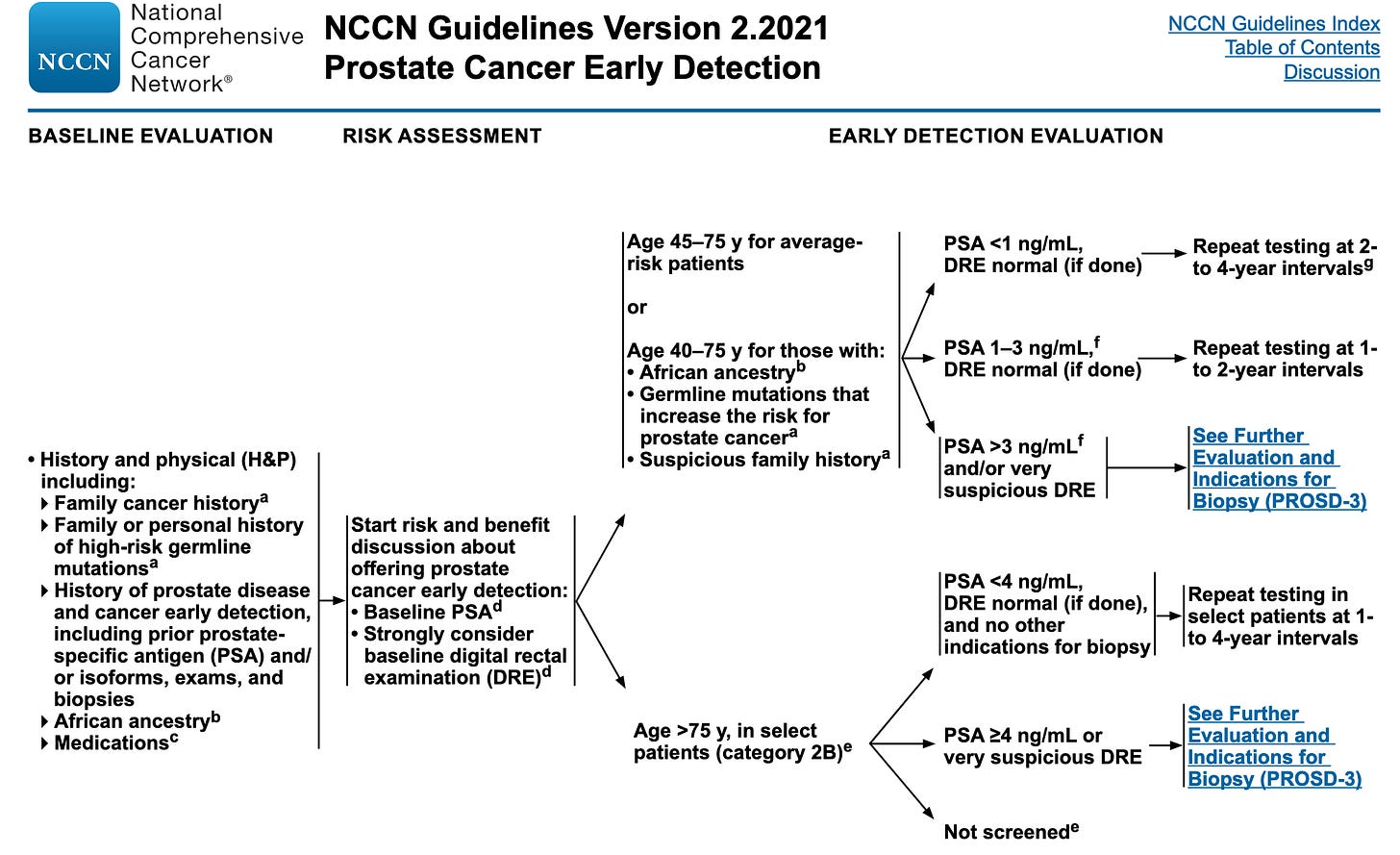

The majority of physicians who treat prostate cancer don’t agree with these guidelines. In fact, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), a not-for-profit alliance of 31 leading cancer centers, came up with its own PSA screening guidelines, which are a lot more complicated.

Not to be outdone, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, which is considered a prostate cancer center of excellence, released its own variation of PSA screening guidelines. It is probably the most nuanced of all, but it has a reasonable rationale behind it.

At the time of my very first PSA test, I didn’t know my brother had been recently diagnosed with prostate cancer, and I was 52 years old. I had been following the USPSTF guidelines. So, I had not been getting annual PSA blood tests and only got the first one because I was having symptoms of prostatitis, and the urologist thought my prostate felt abnormal.

I’m a prime example of why I think the NCCN and Sloan Kettering’s guidelines are more appropriate. However, I’m biased based on my personal experience of developing prostate cancer at an early age. My surgeon said I had probably started developing prostate cancer in my early to mid-40s. I have read case studies of men developing prostate cancer in their mid-30s, but that is extremely rare and usually associated with a high-risk genetic mutation such as the BRCA mutation, which is also found in breast and ovarian cancer.

For men with prostate cancer, seeing a progressive rise in serial prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood levels feels like watching a clock count down to the time of their death. For many men, the first time they are told they have an elevated PSA level is the first time they take a hard look at their mortality. I can honestly say that some of the times during this whole experience when I was most fearful was when I was waiting on a PSA blood test or seeing the results. I call it PSAnxiety. It is extremely anxiety-provoking.

Finding an elevated PSA without having a diagnosis of prostate cancer opens Pandora’s box, meaning it generates an extensive process of unforeseen problems. Your doctor finds an elevated PSA, which, if it is associated with an abnormal prostate exam, will most likely result in a prostate biopsy. Depending on the number of cores taken, the doctor may miss the cancer, and the PSA may continue to rise. Your doctor can augment the PSA test and prostate exam with a slew of other screening tests, including other blood tests, urine tests, and imaging tests.

More tests mean more costs and more tests don’t always give definitive answers. However, more tests can help patients and practitioners make better-informed decisions about what to do next. It’s a conundrum.

As heterogeneous (diverse) as prostate cancer is, so is the approach to screening, diagnosis, and treatment. That’s why evidence-based guidelines have been created based on clinical trials. But as you can see, even the guidelines are heterogeneous!

The average patient who couldn’t begin to understand all of the nuances is left to the decisions made by their doctor, whether or not their doctor has kept up with the latest rapidly changing guidelines. This is why I always recommend consulting a physician at a prostate cancer center of excellence. It’s complicated!

The typical normal range for a serum PSA level is 0 - 4 ng/ml, though normal levels increase as you age. As you can see from the above NCCN’s PSA screening guidelines, once the PSA rises about 3, physicians who follow those guidelines start considering a biopsy.

My preoperative PSA was 47ng/ml. After undergoing what’s called “definitive therapy,” with radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation, my PSA level dropped to 0.9 ng/ml but has continued to rise. Definitive therapy is treatment given with the intent to cure prostate cancer, so if I had been cured, my PSA level should have been 0 ng/ml.

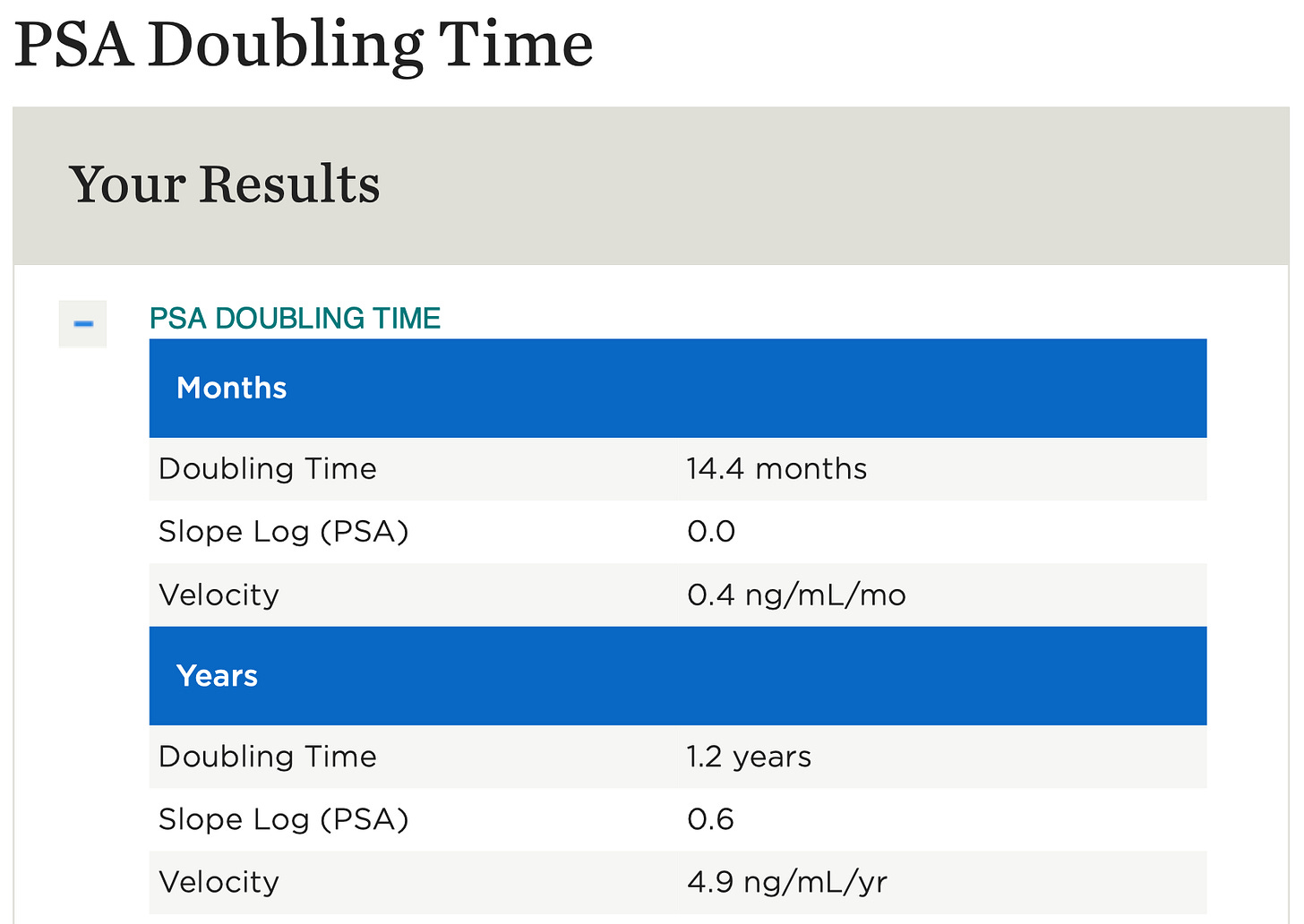

Because we are dealing with prostate cancer, it’s more complicated than simply a rising PSA. You have to look at PSA doubling time (PSADT), the number of months it takes for PSA to increase two-fold. This is because PSADT can be an indicator of aggressiveness, risk for progression, and risk for metastatic disease.

A 2001 review of clinical trials involving PSADT called The Utility of PSA Doubling Time to Monitor Prostate Cancer Recurrence, showed that:

After radiation therapy, metastasis developed in 45.9% with a PSADT shorter than 6 months but in only 8.3% with a PSADT longer than 6 months

After radical prostatectomy, metastasis developed in 33% of patients with a PSADT shorter than 6 months but in only 2% of patients with a PSADT longer than 6 months

Since my PSA level of 0.9 in January 2019, my PSADT has been 6 months, but I did have a six-month period where the rise dramatically slowed. It was during the period from March 2020 to September 2020 that my PSADT went from 6 months to 14.4 months. You can find an online nomogram for calculating PSADT here.

I can’t exactly say what caused it to slow down because I was doing so much at the time—meditation, prayer, juicing, mistletoe injections, eating organic, and regularly exercising. But this was at the beginning of COVID-19, and I do remember significantly upping my self-care since I basically didn’t go anywhere except to work and home.

In retrospect, I know I’m an introvert and introverts like nothing more than time to themselves. At the beginning of the pandemic, besides work, I had a lot of that. As an empathic person, I felt the world slow down during this time and, ironically, felt that comforting despite being part of a pandemic. There wasn’t as much hustle and bustle energy swirling around me.

So, I found life during this time to be less stressful. I used that “extra” time to increase my meditation and exercise. I’m convinced that the significant reduction in my overall stress level during this time is what caused the slowing of the PSADT. Now, if I could reproduce that outside of a pandemic.

In the next newsletter, I talk about innovative ways doctors are screening for prostate cancer. Their goal is to identify men at above-average risk better, identify men with significant prostate cancer earlier, reduce unnecessary prostate biopsies, and better select men who need interventional treatment. These are all things I wish I had known about when I was in the waiting period before my prostate biopsy.

Hi Dr. Holden, Excellent review.. Am sending to my brother. Carry on!! Paula T

What are your thought in this type of treatment? https://www.bitchute.com/video/t6jKhzacS9kz/